In most cases, my client or my client’s opponent has emails that are relevant in a lawsuit and are subject to discovery. But what happens when those emails are in Gmail, Hotmail, Yahoo, etc. accounts? What about Facebook messages? Well, you normally get them from the person who sent or received them. But that raises real questions about whether the person looking for them did what was necessary to actually find those emails. Unsurprisingly, most people don’t look hard enough, or (gasp!) lie to you about what they did or that “I don’t have any emails like you requested.” What then? Can you subpoena the email provider to get them? Well, most courts have said no.

To me that’s absolutely bonkers, and I was shocked the first time I heard the argument. It’s a byproduct of rather clever efforts of Silicon Valley lawyers successfully getting their big tech clients out of the burdens that everyone else has to abide by. And they did so by claiming a law from 1986 (yep, nearly forty years ago) says they don’t have to give you jack squat. (Well, sort of.)

*A quick disclaimer: I sometimes use quotes rhetorically to denote when someone else’ is speaking’s voice that’s not my own–often in my sarcastic way–which doesn’t mean anyone has actually said these things. Any ordinary reader will quickly get the drift from how I write these kinds of blog posts.

The Stored Communications Act

The Stored Communications Act (SCA) came about in the mid-80’s when there were those things called “bulletin boards” and 14.4k dial-up modems (or worse) for those with sufficiently nerdy wherewithal. Most did not have “online” access or even know what “online” meant. And I assure you that in 1986 nobody–I mean NOBODY–in the United States Congress was envisioning today’s tech economy where huge corporations control and store nearly all of our information on their servers which they often do for the privilege of snooping on your stuff. Congress wrote this wonderful piece of legislation that, decades later, Facebook began to say allows them to tell the entire judicial system to piss off: “No, I’m not responding to your subpoena.” (assuming you even get a response, or assuming a judge thinks 3+ months of silence finally warrants a prod). “I don’t care that I might have information that exonerates someone accused of a capital crime.” Or “I don’t care that you’re going to lose your civil case because the fraudster who you asked to produce the emails I have is lying to you.” “Yes, I will spend hundreds of thousands of dollars fighting this all the way to the very top.”

I first received such a lovely response many years ago, circa 2014, in response to a subpoena to Facebook. I was shocked that pretty much every court seemed to be buying the line that no civil process could get information stored ONLY in the hands of these tech giants.

Well, now there’s finally a case that might establish that those companies have to fall in line with the rest of the world and actually produce information when compelled by a legal subpoena. Queue Snap Inc. v. Superior Court. But before we get there, a little case history is in order.

Facebook, Inc. v. Superior Court (Touchstone), 471 P.3d 383 (Cal. 2020)

A few years ago, the California Supreme Court heard a case in which a defendant subpoenaed information from Facebook. Facebook, in its usual fashion, said “yea, no.” Up it went to the appeals court and the state supreme court. But there, the judges punted on the question of whether the SCA provides Facebook with a shield against responding to a subpoena. They focused instead on whether the subpoena was reasonable. But crucially a number of judges said the “the business model issue deserves to be addressed” in a future case.

That argument was novel. Because there was such a huge catalog of (wrong, in my opinion) cases that say tech companies don’t have to respond to subpoenas, a new part of the SCA’s language (18 U.S.C. § 2702(a)(2)(B)) became the focus for attack: it applies only if the provider “is not authorized to access the contents of any such communications.” Well, it seems plain as day that companies like Google and Facebook do access their users’ communications… and then some. They analyze them, sell that data to third parties, and otherwise monetize your communications.

But again, the California Supreme Court didn’t reach the issue, though it did lay the groundwork for a future case to do so.

Snap, Inc. v. Superior Court, 103 Cal. App. 5th 1031 (2024)

Heeding the inclinations of the state’s high court, litigants started to push that argument in the trial courts. And trial court judges agreed. (Yay!) In one case, after Snap, Inc. and Meta, Inc., were ordered to produce their stuff, they sought review in the appeals court (by way of writ of mandamus, I believe). And… the appellate court agreed: “no SCA protection for you! Now respond to that subpoena!” OK, that’s not what the court wrote, but the actual opinion language isn’t all that colorful: “the companies’ ability to access and use their customers’ information takes them outside the strictures of the Act.”

What’s a poor tech giant to do… what with all that effort to provide evidence in the little people’s lawsuits. So, they petition the California Supreme Court… which grants review.

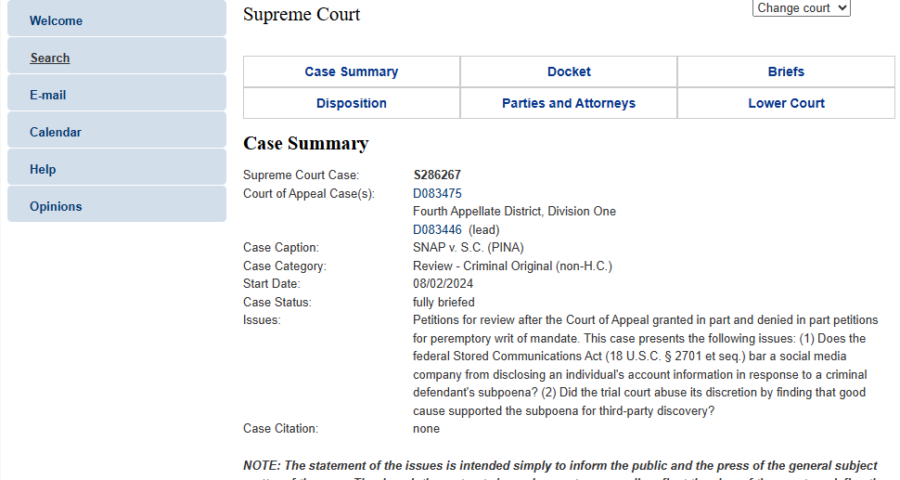

Snap, Inc. v. Superior Court, Case No. S286267 (Cal. 2025)

First, a quick rant: One would think that the State of California, where all these tech companies are headquartered, and with the huge sums of money they have (you know, the “6th largest economy in the world”), that their courts would be able to provide some better online transparency. Nope. Want a direct link to a case docket? No, we’ll tokenize the URL so you can’t. Want to get a copy of that PDF file that we have on our servers? No, we’ll only make them available once oral argument is scheduled. What utter failure of government.

Anyway, Snap and Meta got their wish for a cert grant, and I suspect the court is poised to rule that the SCA doesn’t apply where the company is “authorized to access the contents of any such communications.” That would be an immense blessing for restoring sanity to what people expect in legal proceedings. Obviously those companies aren’t going to just divulge info to anyone, but for them to affirmatively say, “no, not in response to a subpoena” is just absurd. But they’ve had a good run predicated on the text of the SCA which the U.S. Supreme Court hasn’t taken up (though at least one cert petition tried: Colone v. Superior Court, no. 20-1474).

Sooo many amicus briefs have been filed in the pending case (20), with most (unsurprisingly) likely supporting the overbroad reading of the SCA: EFF, Mozilla, Open MIC, Digital Rights Foundation, Tech Global Institute, Wikimedia Foundation, Google, Microsoft, Pinterest, Reddit, X Corp., ACLU, and more.

Professor Chemerinsky and his amici cohort (and a set of criminal defense interests) might be the only ones advocating for the commonsense rule that the SCA doesn’t give the tech companies a free pass to ignore legal subpoena requests for information. We won’t know until oral argument is scheduled, but that’s my bet.

If you want to monitor that case, you can sign up for email alerts (we’ll see how that goes… I’m not all that confident it will work well). https://appellatecases.courtinfo.ca.gov/email.cfm?dist=0&doc_no=S286267 surprisingly, that link does work without the stupid tokenization.

Or if you want to check the docket, plug-in the case number on the form here: https://supreme.courts.ca.gov/case-information/docket-search

If the California Supreme Court does rule that way, then I further predict a cert petition to SCOTUS by Meta.

Leave a Reply